Meet the new boss; same challenges as the old boss

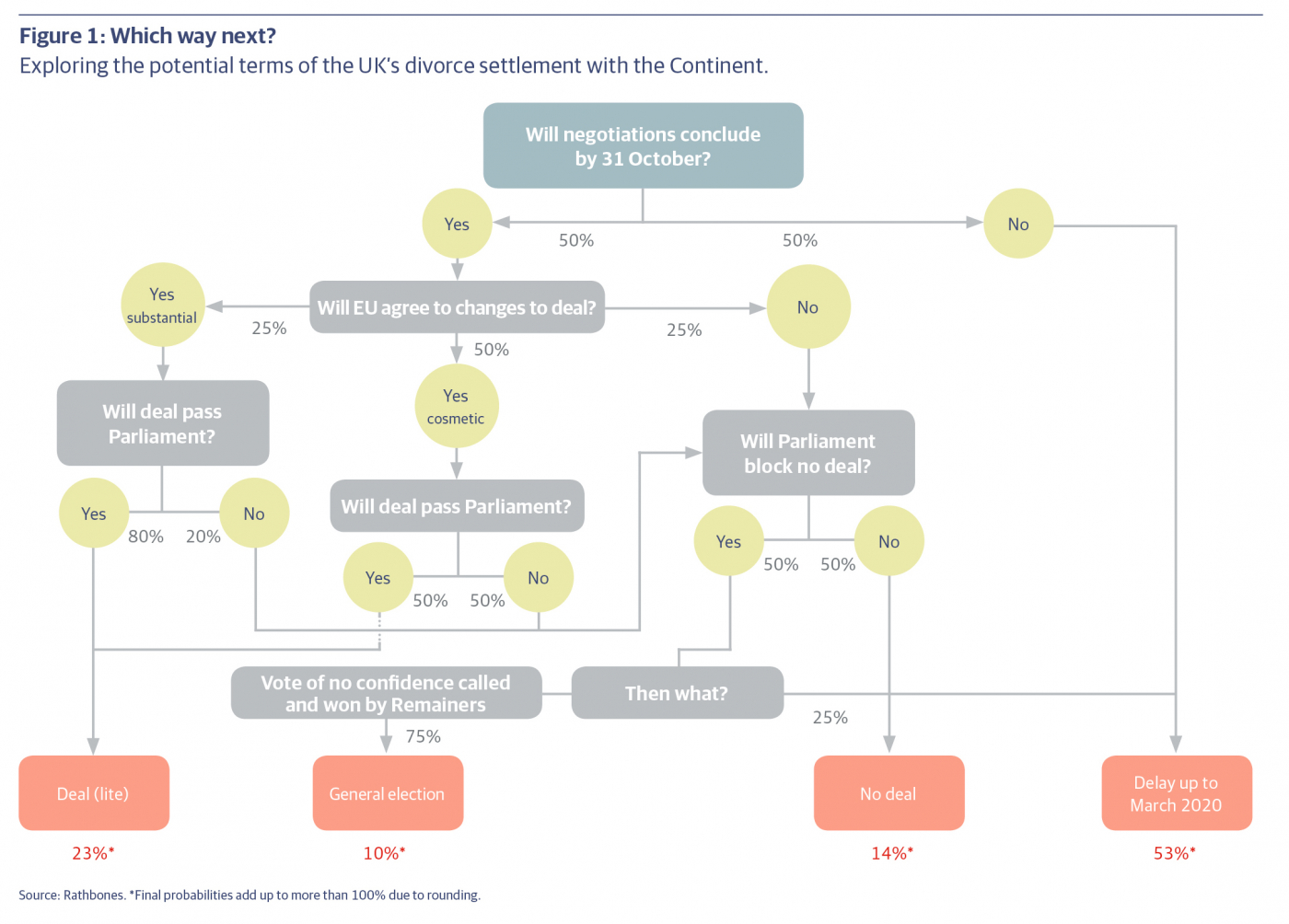

Boris Johnson has become the new leader of the Conservative Party and Britain’s 77th Prime Minister. Brexit has brought him there, and Brexit will dominate his agenda for his first three months in office. We have updated our decision tree accordingly (figure 1), and kicking the can down the road some more remains the most likely scenario.

Of course, there are still many unknowns. The constraints and trade-offs in the contest to win the votes of Conservative Party members – essentially currying favour with staunch leave voters – are very different to the constraints and trade-offs that face Mr Johnson as the new Prime Minister. The emphases in his leadership campaign may shift as a result.

Still, to paraphrase our previous notes, stopping at “we don’t know” is not good enough. Resigning ourselves to a shrug of the shoulders would mean we’re not thinking hard enough. Stopping at “we don’t know” today could make us slow to react tomorrow if the situation clears. And stopping at “we don’t know” is a missed opportunity because there can be quite a lot of information in “we don’t know” if we break down the overarching conundrum into a sequence of smaller questions. When we work our way down the tree to the possible outcomes in red and calculate their conditional probability, we find that they are not all equally likely, even if we have expressed “we don’t know” mathematically at a number of nodal points. And that little extra knowledge – that some outcomes are more likely than others – is important for investors, because financial markets are nothing if not probability-weighting mechanisms.

The road to Halloween

Mr Johnson takes on many of the same challenges faced previously by Theresa May. He will have to contend with a dwindling government majority. The Conservatives are likely to return from the summer recess with a working majority of three (if the Brecon and Radnorshire by-election on 1 August goes to the Liberal Democrats, as is widely expected). That makes it very difficult for Mr Johnson to get Parliament to stand by and allow his threat of a ‘no deal’ – “do or die” – Brexit to come to pass. April’s Cooper-Letwin Bill, whereby Parliament took control of Commons business, has set a profound precedent and its implications are likely to be repeated if leaving the EU without a deal – the default option – looks increasingly likely as the current deadline of 31 October approaches. The vote on 18 July to make proroguing Parliament extremely difficult established another legal barrier to ‘no deal’.

To be sure, it is not off the table. But as we work through our decision tree, it becomes clear to us that ‘no deal’ is not as likely as some commentators contend. Please note, our exercise is designed to take us no further than 31 October, hence ‘delay’ is an outcome. The probability of ‘no deal’ occurring eventually is therefore higher.

Mr Johnson has said that leaving without a deal is not his preferred option and that it has a million-to-one chance of occurring. This makes it rather clear that the embrace of ‘no deal’ is a negotiating tactic – and you don’t have to be an expert in game theory to see that this weakens its ability to function as one. In Mr Johnson’s own words, from an interview with the BBC: “And the way to get our friends and partners to understand how serious we are is […] to prepare confidently and seriously for a WTO or ‘no deal’ outcome. You’ve got to understand, Laura, listening to what I just said, that is not where I want us to end up. It is not where I believe for a moment we will end up. But in order to get the result that we want, in order to get the deal we need, the commonsensical protraction of the existing arrangements until such time as we have completed the free trade deal between us and the EU that will be so beneficial to both sides [sic].”

The final line is important. He wants existing arrangements to continue until a trade deal is made. He repeated this in an interview with TalkRadio, adding that the time it would take to negotiate a trade deal would also be used to solve the questions of the Northern Irish border. The current agreement already accommodates the protraction of existing arrangements until the end of 2022. The tweak required to mirror the new PM’s language seems minor, and something the EU would likely agree to. We wonder if the UK might push for a formal link between achieving a future trade deal and the payment of the UK’s financial settlement – the so-called divorce bill. This might also be something the EU would likely agree to. But it is not clear that the hardest Brexiters within the Conservative Party feel the same way. As such, we estimate a 23% chance of the new government passing a withdrawal agreement. Remember, the cloud of uncertainty will not fully disperse in this scenario: the withdrawal agreement leaves most of the terms of the UK’s commercial relationship with the EU to be decided.

We think it is unlikely that the EU will agree to any more substantive changes. Major concessions are likely to be vetoed by French President Emmanuel Macron. That said, our recent research trip to Brussels revealed a willingness from the EU Council to grant an extension of the current deadline to March 2020. The end of March 2020 is the latest date that the EU’s multiannual financial framework for 2021–27 could be signed off, and a deal with the UK must be reached by then so that its contributions to the budget can be incorporated. The EU Council controls the timetable, and its president-elect, Charles Michel, is a little more amenable to the idea of a hard Brexit than some of his colleagues (“at least it would be clearer,” he has said). But he doesn’t take office until December, and the incumbent president, Donald Tusk, would likely grant an extension in our opinion. We have a 53% probability of extension.

Mr Johnson has said that the UK will definitely leave on 31 October. Yet when prompted by interviewers he has refused to promise to resign if this doesn’t occur. Certainly, there is very little time for Mr Johnson to resolve Brexit as it stands. The leadership contest has finished just before Parliament’s summer recess, which lasts until early September. The new government will therefore have just seven weeks before the October deadline once it reconvenes. An extension would be expedient. It is possible that the most staunchly pro-Brexit MPs will call a vote of no confidence if he doesn’t deliver, but we think this risk is negligible – what would they have to gain?

Conversely, a vote of no confidence could occur if ‘no deal’ is looking likely. Ken Clarke, Dominic Grieve and Phillip Lee have said they are willing to vote against the government in a no-confidence vote to avoid ‘no-deal’. Philip Hammond has countenanced doing the same. It seems unlikely that pro-Brexit Labour MPs will support Mr Johnson. His government could attempt to run down the clock on negotiations so that there is no time for a confidence vote, but, as we discuss above, Parliament is likely to intervene.

The loss of a confidence vote will lead to a general election if a repeat vote is not won within 14 calendar days. There must be at least 25 working days between the dissolution of Parliament and polling day, which means that a vote of no confidence must be tabled before 9 September – the fifth working day after Parliament returns from the summer recess – if a new government is to be established before 31 October. This seems unlikely. To our knowledge, there is no precedent for what might happen if the government loses a confidence vote, but remains in charge on the day the UK is set to exit the EU. The route to a second referendum before a general election is harder to envisage now compared to a year ago.

As the polls stand, a general election could result in a Labour-led coalition or minority government, which would undoubtedly unnerve investors. For further information on the key policies tabled by the Labour Party, please refer back to our report Oh! Jeremy Corbyn.

Investment implications

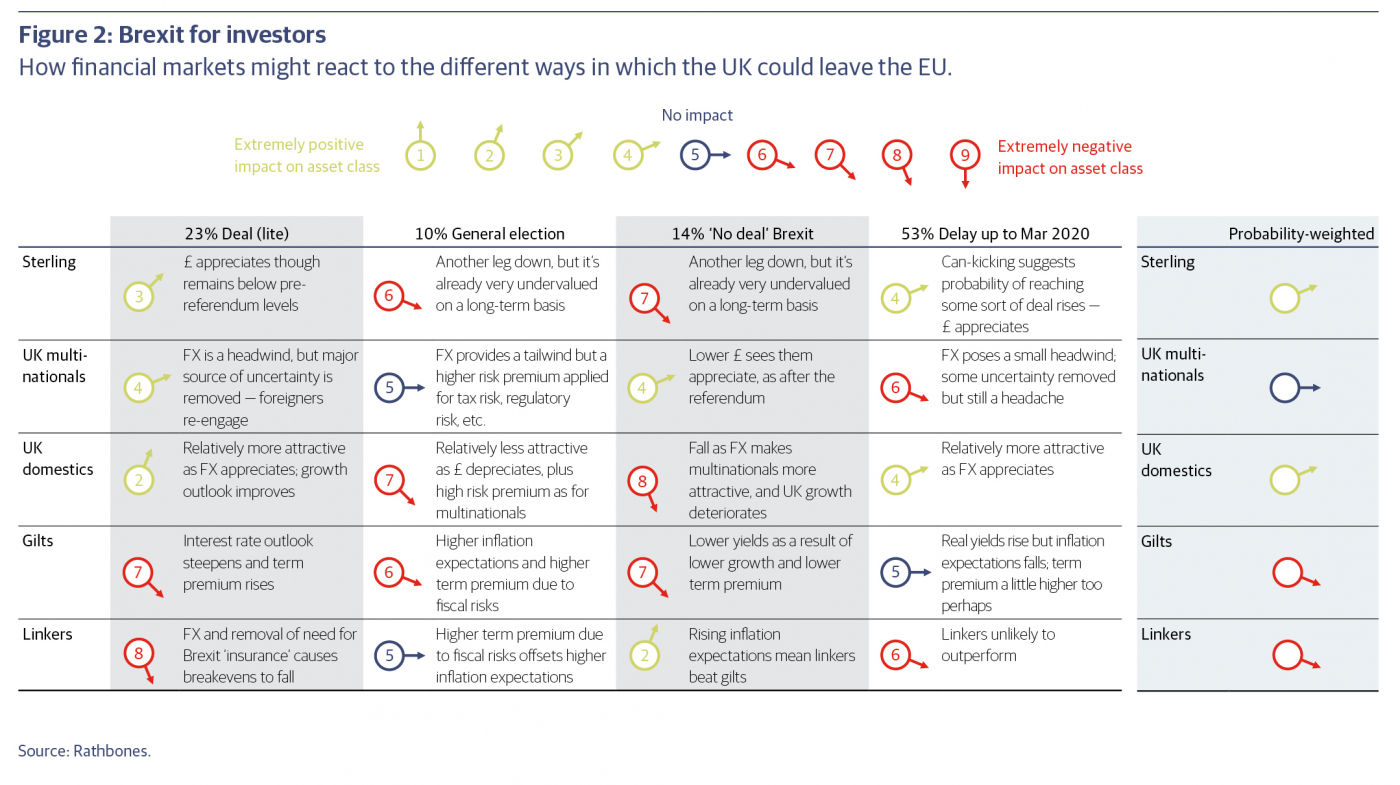

Figure 2 assesses the impact of each outcome on five key asset classes. Brexit is not a globally systemic event and non-UK markets are unlikely to move much in response. Only 3% of the revenues earned by US companies originate in the UK; just 6% for non-UK European companies. Even FTSE 350 firms make just 25% to 30% of their revenue in the UK. We use a nine-point scale, where ‘1’ represents an extremely positive impact on the asset class, ‘5’ no impact and ‘9’ an extremely negative impact. We also represent this graphically using arrows angled between 0 and 180 degrees. On the right of figure 2, the orientation of the arrows represents the probability-weighted average outcome.

The table contains brief explanatory notes, but some further reasoning may help. The exercise shows that exposing portfolios to considerable currency risk by overweighting overseas assets is perhaps not the best strategy given the current political outlook. “We don’t know” doesn’t lead us to “sell the UK”.

We believe that financial markets are pricing in a much higher chance of a ‘no-deal’ Brexit than our decision tree suggests. On a long-run basis – the only timeframe over which we believe currency forecasts can be made with any certitude – sterling appears very undervalued (using purchasing power parity or our own framework, which looks at relative prices, relative productivity and relative savings). This holds even when we hypothesise a highly adverse scenario for the UK economy. If Brexit were abandoned, we expect the pound would go up by more than it would fall should a hard Brexit be confirmed.

A stronger exchange rate would normally weaken shares of multinational companies listed in the UK, holding all other things equal. Remember how the FTSE 100 outperformed immediately after the referendum and indeed for the rest of 2016, before underperforming dramatically for the next 12 months or so as foreign investors sold UK companies indiscriminately (regardless of their exposure to UK revenues). But there is a good case for a softer Brexit resulting in both a stronger pound and a stronger FTSE. That’s because the FTSE is so under-owned by global investors. The equity risk premium applied to the FTSE 100 – the compensation investors demand for assuming the risks associated with future earnings – is as high today as it was during the financial crisis, unlike elsewhere in the world. A number of key UK sectors are trading at discounts to international peers.

The market in interest rate derivatives perhaps offers the clearest indication that markets are over-weighting ‘no deal’. Throughout June and July, several members of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee emphasised that while rates would likely be cut in the event of ‘no deal’ they would gradually rise in any other scenario. Yet the derivatives market is pricing in one rate cut by July 2022!

The economic backdrop

Since the referendum, the UK economy has grown at an historically weak rate – weak, also, by international comparison. Business investment has been particularly hard hit. A recent study by the Centre for Economic Performance estimated a total increase in UK investment in the EU of £8.3 billion over the period between the referendum and the end of September 2018. To the extent that this investment would otherwise have taken place domestically, this represents lost investment for the UK, and is difficult to explain by anything other than a Brexit effect. Higher outward investment has been accompanied by lower investment into the UK from the EU, amounting to £3.5 billion of lost investment.

The outlook has weakened further in the last few months. The Bank of England’s (BoE) investment intentions survey indicates a contraction of business investment for the first time since the immediate aftermath of the referendum. This is consistent with a swathe of leading indicators of broader economic activity that point to extremely weak growth or contraction. Of course, the rest of the world is also undergoing something of a slowdown (see our latest quarter-end outlook for more information), but the UK looks weaker than most Western economies.

Another BoE survey conducted between 23 April and 28 May found that half of firms said that they implemented contingency plans in the first quarter ahead of the first deadline and do not plan to do any more, while just over 25% firms said that they will do more ahead of October. Before the initial March deadline, the economy received a temporary boost as firms built up inventories as insurance against disruption. This survey suggests that the economy will not experience the same boost again. That said, it was conducted before the new leadership contenders started to talk up their intentions to take Britain out with no deal.

The economy’s fate rests on household behaviour. From April to June, retail sales grew above their historic average rate of growth. This is because inflation-adjusted wage growth is stronger than at any time since the financial crisis. Our model for nominal wages, which looks at under-employment and productivity, suggests the current rate of growth is unlikely to be sustained, but should remain relatively high. Inflation is also likely to stay close to the BoE’s 2% target, despite the renewed weakness in the pound.

The changes in income tax thresholds for 2019–20 announced in the Spring Statement have increased post-tax income too. Mr Johnson has promised further tax cuts for higher-rate tax payers. These appear generous, costing the government £9 billion a year, but only benefit about 8% of Britons, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies. As the beneficiaries are already relatively wealthy, some of this stimulus is likely to be saved.

That is especially likely considering that consumer confidence has fallen far below the average for the post-referendum period. Therefore the biggest risk to the economy is a rise in the household saving rate. The headline measure of household saving (4%) is very low compared to the 20-year average (8%). But much of this gap can be accounted for by compulsory pension saving under the auto-enrolment scheme. Strip out pensions, and the saving rate has risen quite substantially since spring 2017. At 1% it is closer to the historic average of 2%, but between the financial crisis and the referendum it averaged 4%.

The historically close relationship between unemployment and savings behaviour means that the outlook for employment is key. The unemployment rate at 3.8% is the lowest since 1974. But job creation has slowed: were it not for continued growth in self-employment, the economy would have shed jobs between March and May. The number of employee jobs fell by the largest amount since 2011. Job vacancies have also declined to a 13-month low. The BoE’s employment intentions survey has fallen to the weakest level since the referendum, but this may, in part, reflect recruitment difficulties, and so it should support wage growth.

This article has been written by Rathbones International, one of the UK’s leading providers of investment management services for individuals, charities and professional advisors, working together with Unity Financial Partners to provide wealth management solutions to its clients both in Italy and abroad.

The increased likelihood of a No Deal Brexit on 31 October has important implications for British citizens residing in Italy.

In order to protect your citizens’ rights (right to stay, access to healthcare etc) it has become much more important to be correctly registered as a resident in Italy, as frequently reiterated by the British Embassy here in Rome (see also our article on regularising residency of 11 December 2017 on Britishinitaly.com)

Italian residency has significant implications for British people holding financial and/or real estate assets in Italy, in the UK and elsewhere.

If you have a UK pension plan you should check how withdrawals will be treated in Italy for tax purposes and whether your provider is capable of paying you in Euro to a non UK account.

If you hold UK based direct investment funds and Individual Share Accounts (ISAs) these are unlikely to be the most tax efficient way to manage your savings as an Italian resident.

Where, how and in what currency you hold your financial assets are also never simple choices.

Many British citizens understandably rely on their “tried and trusted” financial advisor based in the UK to provide advice on how best to manage their pensions and investment plans when living abroad but a UK based advisor is very rarely able to provide an informed opinion on the suitability of these assets for a British Citizen resident in Italy.

For many years, Unity Financial Partners, regulated both in Italy and the UK, has been advising its British clients in Italy to help structure and manage their pensions and savings so as to be compliant and tax efficient for local residency as well as portable should circumstances change.

Unity is able to offer internationally secure and tax efficient solutions in Euros, Sterling or Dollars, managed by reputable and experienced English speaking asset managers, held in either the UK or in an EU or EEA country outside of Italy.

Please contact us now to discuss any of this further:

http://www.britishintaly.com/contact-us